Rabbi Twerski lamented to me that it’s not uncommon to hear of people who experience a decline in their religious observance as a result of their participation in Twelve Steps meetings. He was looking for a way to address this phenom- enon and ended up sending me an article on the topic, which he asked me to publish. (He also sent some questions and answers on the topic, which were published in the book we put out together with him in 2016 called Teshuvah Through Recovery, Menucha Publishers).

A number of people have raised the issue of the relationship of the Twelve-Step Program to Yiddishkeit. Some have indicated that they were frum during their active addiction but that they dropped their Yiddishkeit during the course of the program. In order to address these issues, I think I must tell you something about myself. I think that problems may arise because of distortions of both Yiddishkeit and the Twelve Steps. I gave some autobiography in Generation to Generation and in Gevurah: My Life, Our World, and the Adventure of Reaching 80.

I was born into a chassidic family. My father was a rebbe in Milwaukee. Our shul was comprised primarily of first-generation Russian immigrants. Having had no secular education in Russia, and having no access to the professions, they wanted to give their children what they lacked. Consequently, they gave their children a secular education and essentially neglected teaching them Yiddishkeit. I did not have a single shomer Shabbos friend. My friends were the people in shul, all older than fifty. They were wonderful people, sincere in their Yiddishkeit.

I heard many stories about my ancestry, great Talmudic scholars and tzaddikim. These were the models I had to live up to.

I thoroughly enjoyed Yiddishkeit. Shabbos and Yom Tov were delights. I never felt the restrictions of Torah to be a stress. Although I was taught that there was a punishment for aveiros, I never thought that God was punitive. Even as a youngster, I felt that the punishment was inherent in the sin. If you put your hand in the fire, the natural consequence was a burn, not a punishment. Sins were detrimental to a person, and the painful consequence of a sin was in the act itself, not a punishment. Yes, God may punish, just like a loving father may have to spank a two-year-old for running into the street, because the child cannot understand the danger involved. Our intellect, even as mature adults, is limited. We may not be able to understand what is wrong with mixing meat and dairy.

God has no needs. The Midrash says that it makes no difference to God how an animal is slaughtered. The laws of shechitah and all other Torah laws are for the benefit of man, not of God. But our limited intellect may not be able to understand why treif food is harmful to us, and in this respect, we are similar to the two-year-old who cannot understand why he cannot run into the street to retrieve his ball, so we have to be warned with a “spanking.” If we can reach the understanding that the Torah laws are not for God’s benefit but for our own advantage, we need not worry about punishment.

Fast forward to age twenty-one, when I became a rabbi in my father’s shul. Some of the old crowd had passed on. Many of the congregants had warm feelings about Yiddishkeit but were not observant. They had their children become bar mitzvah, followed by a celebration in a treif hotel. I performed weddings that were followed by treif dinners. After three years of this, I knew I could not take this for life, and went to medical school, followed by psychiatric training.

I took the position as medical director of a huge psychiatric hospital, which had a thirty-bed alcohol detox unit, better known as the “drunk tank.” Drunks were dried out for several days and were told to go to Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), which very few did, so we ended up being a revolving-door drunk tank.

In my book From Pulpit to Couch, I related how I got to AA. Here is the story:

My Teacher, Isabel

I learned many things at meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous. Inasmuch as I never drank, why did I attend meetings of AA? Here’s how it happened.

I was in my second year of psychiatric training when I received a call from the psych emergency room. A woman said she had to see a psychiatrist promptly and could not wait for an appointment.

Isabel was sixtyone. She was one of three daughters of an Episcopalian priest. Isabel began drinking late in adolescence, and at twenty she was into very heavy drinking. She married and had a child. When the child was three, her husband said, “Make your choice. It’s either the booze or the family.”

“I knew I could not stop drinking,” Isabel said, “and I wasn’t much of a wife or mother. It was only decent to give him the divorce he asked for.”

At sixtyone, Isabel was attractive, and she must have been stunning at twentyeight. Free and unattached, she began serving as an escort to some of Pittsburgh’s social elite. She had a beautiful apartment, the latest in fashions, and all the alcohol she wanted.

After five years, the alcohol began to cause behavioral changes that made Isabel undesirable company for her clien-tele. She then began serving a lower socioeconomic clientele, and very rapidly deteriorated. She was soon living in fleabag hotels and prostituting.

Every so often, Isabel was found passed out and taken to a hospital for detoxification. She attended the AA meeting in the hospital, and upon discharge promptly resumed drinking. When I assumed the position as director of psychiatry at St. Francis Hospital, I looked up Isabel’s record. Between 1938 and 1956, Isabel had been detoxed at this hospital fifty-nine times! At another hospital that offered detox, she had twenty-two admissions. I was unable to get any information from other hospitals where she had undergone detoxification.

Isabel’s family was horrified by her behavior and disowned her. Her phone calls to her sisters were answered with a brusque “Don’t you dare call me again” and a hangup.

In 1956, Isabel approached a lawyer who had helped her out of some alcohol-related jams. “David, I need a favor,” she said.

“Good God!” the lawyer said. “Not again! What did you do this time?”

“I’m not in any trouble,” Isabel said. “I want you to put me away in the state hospital for a year.”

At that time Pennsylvania statutes had an Inebriate Act, under which a chronic alcoholic could be committed to a state hospital for “a year and one day.” This law had been used by families who wanted to get a chronic alcoholic out of their hair. No alcoholic had ever asked to be put away for a year.

“You don’t know what you’re asking for,” the lawyer said. “You’re crazy.”

“If I’m crazy, I really belong in the state hospital,” Isabel said.

Isabel continued to press her request, and the lawyer finally took her before the judge and had her committed to the state hospital.

After a year of sobriety, Isabel left the state hospital and promptly went to an AA meeting. Someone gave her a few nights of shelter, and she soon found a job as a housekeeper for a nationally renowned physician.

The doctor was retired and was a chronic alcoholic. Many times Isabel had to lift him off the floor and put him in bed. He sat on the board of several foundations and was periodically called to testify at Senate hearings. Isabel would receive a call from the doctor’s children: “Dad has to be in Washington in two weeks. Get him into shape.”

Isabel would detox the doctor, get him a haircut and shave, and put him on the plane to Washington.

“Now don’t you drink on the plane or in Washington,” she said. “When you come back tomorrow, I’ll be waiting for you with a bottle.”

The doctor obeyed like a well-trained puppy.

I had never heard anything like this before. My first career was as a rabbi, and seminary did not teach me anything about alcoholism. Medical school was no better. I learned much about some rare diseases, but nothing about the most common disease a doctor encounters. In my psychiatric training I was learning much about mental illnesses, but alcohol and drugs were never mentioned.

I was so fascinated by Isabel’s story that I neglected to ask her what her acute emergency was. As a fledgling psychiatrist, I knew that there had to be motivation for a person to seek help. What could possibly have motivated Isabel to take so drastic a measure, to put herself into a state mental hospital for a year by a court order? I had to discover her reason, so I told her to come back in a week for another session.

In the next session I heard some more interesting stories. Inasmuch as I did not have a clue about her motivation, I had her come back the following week. To make a long story short, I saw Isabel once a week for thirteen years. One night, at age seventy-four, she died peacefully in her sleep.

I was curious how she was managing to stay sober. It was obvious to me that medicine and psychiatry had no effective treatment for alcoholism. What was her secret?

“I go to meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous,” she said.

In 1961, none of the celebrities had revealed that they were recovering alcoholics. Few people outside of AA knew anything about it.

“What happens at these meetings?” I asked. “Who pro- vides the treatment?

“We have speakers’ meetings and discussion meetings, and we share our experiences,” Isabel said.

“Do you have psychiatrists or psychologists there?” I asked.

Isabel said, “There is one psychologist who shows up occa- sionally, but he’s still drunk most of the time.”

“Look, Isabel,” I said. “Some kind of treatment must be going on at these meetings if they are keeping you sober. Can I come and see for myself?”

“Sure,” Isabel said.

That week she took me to my first AA meeting.

The first thing that struck me at the meeting was that

there was no stratification. Everyone was equal. No one could become president of the organization, and furthermore, money could not buy any special privileges.

As a rabbi, part of my job was to raise funds to cover the annual budget. Money came from the congregants’ donations. People of lesser means made smaller contributions, and wealthier people made substantial contributions. I liked everyone equally, but I had to handle the large donors with silk gloves. I could not risk offending them, lest they leave for another congregation. Wealthy congregants received special treatment.

It is said that “before God, everyone is equal.” God can afford to treat everyone equally. He doesn’t have to make mortgage payments each month. I did.

Any organization that is dependent on contributions is in the same situation. People with money or political clout are given preferential treatment. What impressed me about AA was that once people entered the room, everyone was equal. The rich received no special attention. Sometimes a poor person was in the position of helping a wealthy person. Nor did academic status count. A fifth-grade dropout and a PhD were treated equally. I had never encountered anything like this!

Here is an example of AA’s independence. I received a call from a man who said that he wanted to make a contribution of $10,000 to AA in memory of his late sister, who had enjoyed fourteen years of sobriety with the help of AA. He asked me where to send the check.

I called several people in AA, and when no one could help me, I called the AA central office.

“Don’t send the check here,” they said. “We can’t do any- thing with it.”

“Then how can this man make a contribution?” I asked.

“He can cash the check at the bank and go to a meeting. When they pass the basket, he can put the money in.”

“You want him to put $10,000 in cash in the basket?” I asked.

“Yes,” was the answer. “But if he’s not in the program, they might return it to him.”

Never before and never since have I come across an organi- zation that refuses donations.

My fascination with AA brought me back to more meetings. As I became familiar with the Twelve Steps for recovery, I concluded that they were a formula for mature, responsible living. There was nothing unique about alcoholics that made the Twelve Steps specific for them. I found that virtually every character defect that can be found in alcoholics can also be found in non-alco- holics, although they may be less pronounced. The Twelve Steps were a way for proper living, and I could apply them to myself.

So began my involvement with AA. I have attended meetings in many cities in the United States and in many countries I have visited. I can find friends in a community where I do not know a single person.

I would like to share with you what I have learned from AA. In case you happen to be a recovering person who thinks that all AA can do is keep you from drinking, you are missing out on a great deal of valuable knowledge.

What about the secret of Isabel’s motivation to put herself into a state hospital? I never did solve that mystery in the thir- teen years of therapy. I was left to my own devices to guess at it, and here is what I think.

Do you know how a volcano is formed? Deep down at the core of the earth, there is melted rock that is under extreme

pressure. Over many centuries, this lava slowly makes its way through fissures in the earth’s crust to the surface. Once it breaks through the surface, the lava erupts.

I believe that at the core of every human being there is a nucleus of self-respect and dignity. For a variety of reasons, this nucleus may be concealed and suppressed. Like the lava, it seeks to break through the surface and be recognized. Once it breaks through into a person’s awareness, one may feel, “I am too good to be acting this way. This behavior is beneath my dignity.” I think this is the “spiritual awakening” to which the Twelfth Step refers.

I think that this is what happened to Isabel. For years she had been blind to her self-worth and saw nothing wrong with her alcoholic behavior. Then one day, the nucleus of self-respect that had been buried deep within her broke through the sur- face, and she realized that she had no right to demean herself.

Why the state hospital? Let me share a personal experience.

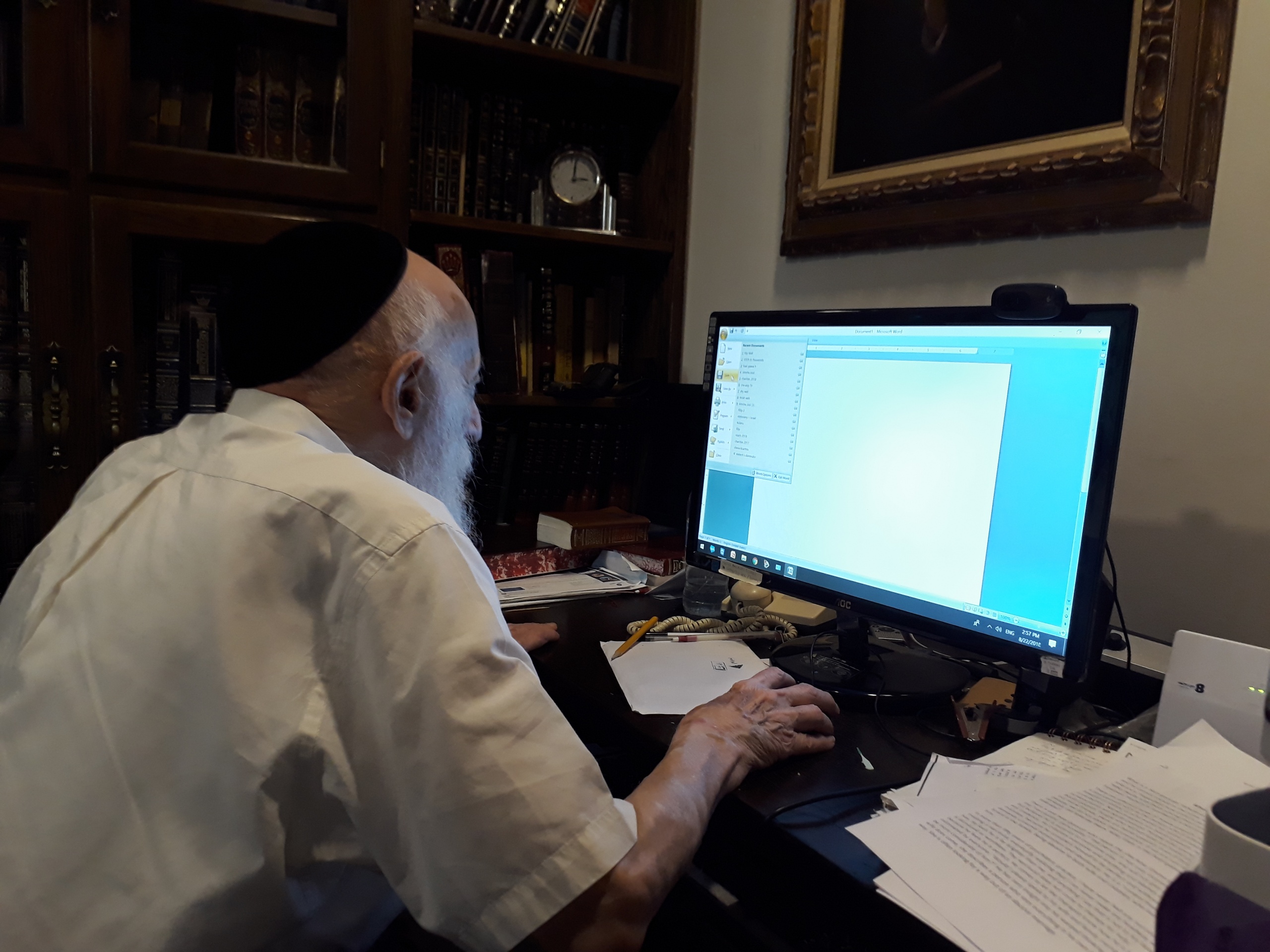

I do most of my writing early in the morning when my mind is rested. One time, the publisher told me that they were mov- ing up the publishing date and that I had to complete the book sooner. That meant that I had to get up an hour earlier.

I set my alarm clock for 4:30. When it rang, I did what most people would do: I turned it off for just five minutes more of sleep. Of course, I woke up two hours later.

Several months later, I had to deliver a lecture in Washington, DC, at 10 a.m., which required my taking a 7 a.m. flight. To make this flight, I had to be up at 5 a.m. I set the alarm clock for 5 a.m., but remembering my tendency to turn it off for “just five minutes” more sleep, I realized that I might miss my flight. I took the alarm clock off the night stand and set it in the far corner of the room so that I could not turn it off from the bed. The next morning I awoke at 5 a.m. and walked across the

room to turn off the alarm. I was then able to stay awake and make the flight.

On both occasions I had an awakening. The first awakening did not last long, because I went back to sleep. The second time, I did something to avoid going right back to sleep. I made the awakening last.

Some people may have a spiritual awakening, but it does not last. Isabel knew that unless she took some measure to make her awakening last, she was likely to revert to drinking. The only way she knew to keep her awakening alive was to put herself out of reach of alcohol for an extended period of time. The state hospital was her only option.

I am indebted to Isabel for bringing me to the Twelve-Step Program. What was the crisis that brought her to the emergen- cy room that day? There was no crisis. Why, then, did she seek an emergency appointment just on the day I was on emergency duty? Perhaps she was sent there to introduce me to AA. But who could have sent her? Your guess is as good as mine.

Realizing that just drying someone out was not enough and that few people after detox went to AA, I militated for a rehab, and together with St. Francis Hospital, we opened Gateway Rehab Center in 1972.

Addiction is a disease, and treatment is necessary to bring a person to health. The Twelve-Step Program can bring a person to health. But is it enough to be just healthy? Yiddishkeit teaches that a person must have a purpose in life. Addiction makes it impossible to reach a purpose, but overcoming the addiction is not an ultimate purpose in life. If a person has a serious physical illness, he certain- ly must be treated, but if he recovers, is that all there is to life?

Yiddishkeit teaches that a person has a mission in life. The first chapter in Mesilas Yesharim is “Man’s Obligation in His

World.”

Having studied much mussar, I felt that Bill Wilson pla-

giarized mussar in developing the Twelve-Step Program. In my book, Self-Improvement? I’m Jewish, I show the essential identity of the Twelve Steps and mussar.

Why is it that some frum people, even if they were well versed in Torah and mussar, fell into the trap of addiction and recov- ered with the Twelve-Step Program, whereas mussar did not help them? I think the answer is simple. A person who is sincere in recovery leaves a Twelve Steps meeting with the knowledge and feeling, “If I deviate from this program, I will die.” In our davening, we say, “Ki heim chayeinu” — that Torah and mitzvos are our very life. But while we say this, I doubt that many people actually feel, “If I deviate from mussar, I will die.”

An example: An alcoholic came to rehab because his employer gave him a last chance: one more drinking binge, and he would be fired. He was deathly afraid of losing his job. He attended AA regularly. When he was eight months sober, he called me in a panic. He had attended a friend’s daughter’s graduation party, and the friend offered him a drink, which he refused, but he did accept a glass of punch. After one swallow, he realized that the punch was spiked. He called me in a panic.

“What should I do, Doc? I accidentally swallowed some al- cohol. Should I put myself in the hospital? I’m afraid I’ll end up drunk!”

I told him to call his sponsor and get to a meeting.

Now let’s look at this case. A frum person has been enjoying a particular candy bar for years. This time, he was playing around with the wrapper and noticed that the hechsher symbol was gone. If the hechsher was removed, it was because they had added a nonkosher ingredient. He feels badly that he might have eaten something nonkosher, but does he call his rabbi in a panic?

“Rabbi, I think I might have eaten something treif! What should I do? I’m afraid that this might lead me to eating pork on Yom Kippur!”

You see, the addict knows that even an accidental slip can be fatal. The frum person may have learned that “sin begets sin” but does not believe it the way a recovering addict does.

A recovering person may find the conviction in the Twelve -Step Program to be more intense and have greater sincerity than he experienced in Yiddishkeit. The response to this should not be to relinquish Yiddishkeit; rather, the necessary response is to increase knowledge and understanding of Yiddishkeit and to practice it with feeling rather than as routine.